This was the day she had been waiting for, a day she would remember for the rest of her life, a day she hoped would go down in history—and it did.

On Dec. 3, 1971, 21-year-old speech pathology major, Irma Camacho, and 29 others sat in protest, blocking the entrance to UTEP’s Administration Building. They were fed up with the lack of Chicano representation in the faculty at UTEP.

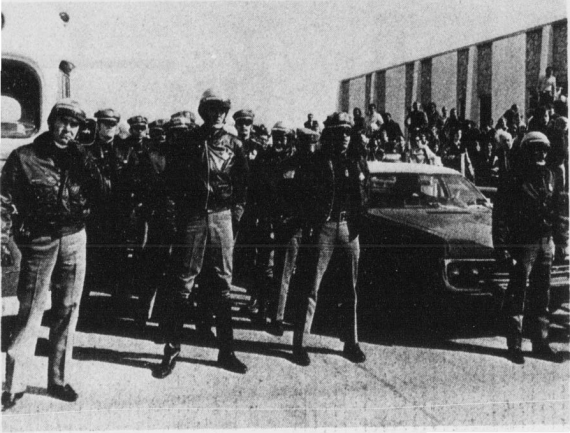

While they sat, thousands of others chanted, marched and took over University Avenue. The students set effigies of then UTEP President Joseph Smiley on fire. Law enforcement responded to the crowd with tear gas and a bus to detain them.

Irma Camacho,

the idealist

Camacho was one of 34 students who were arrested. She is now a psychology instructor at El Paso Community College.

Q: Can you describe how the events unfolded that day?

A: It was incredible. There was a group of students that sat in at the Administration Building. We heard that the president was out of town and the interim (Vice President for Student Affairs Gary Brooks), instead of negotiating with the students, he brought in the Texas Rangers and local police.

We heard them marching in, they brought a bus on campus to try to put us all on it, and then some of the students pulled some plugs or did something to the motor so the bus wouldn’t move.

Then they came through with police cars and they dragged us all off. I think it was two or three police cars and we wound up being booked downtown. We were out within a few hours, so that wasn’t too bad.

Q: Why did you decide to get involved with the protest?

A: I felt that as a student, it’s important to question what’s happening within the university or within any institution at any point in history. There isn’t a place for complacency because that’s what being an educated person is about—to question the process, to question what’s happening and to question the policies that affect a large number of people. I really hope that that stands as an inspiration.

There were a lot of demands that the students had. One of them was to have more Chicano faculty. Back in the day, there weren’t that many. We had been very close to some of the faculty members and we wanted them to attain tenure, or at least be considered for it. We knew that the tenure process is a very elite activity, but we felt that there were those people who should be considered because of their support for the students.

We also never thought of education as something that was just a personal journey for us to achieve occupational and economic independence. We were very involved in what was happening in the community.

A big part of (the protest) was wanting the university to see that it wasn’t just an ivory tower in El Paso, but rather that the realities of the community are very important. The university should be a place to reflect what is needed in the community.

Raimundo Sarabia,

the organizer

He didn’t plan on having such a large turn out, he said. He just wanted something to change.

Raimundo Sarabia was the chairman of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán at UTEP in 1971, a student organization that was new to campus. He is now a housing counselor for Prosperous, a branch of GECU that helps people plan for the purchase of a home. He said the group organized the protest at the Administration Building after several other tactics yielded no response.

MEChA originated at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1969, when a group of more than 100 students met to create a higher education plan for Chicano and Chicana students.

Q: How did you get involved with this movement?

A: It started when I was a student at Coronado High School. At the time that I went, there were very few Hispanics and I felt some discrimination there that didn’t sit well with me.

Basically, I got involved with the movement because, through school, I learned that everything was equal, but my life experience at Coronado showed me that it was unequal. Myself and two other guys decided to investigate what went on at Coronado—for example, we found out that they were busing children from more typically Hispanic areas and sending them all the way out here to Coronado and to El Paso High School.

We discovered that the district used to fund Anglo schools better than Hispanic schools. They used to send the newer teachers to the Anglo schools and the older teachers to the Hispanic schools. We did our research and sued them and we won—10 years later—but we won.

Based on that experience, I noticed as well that the same thing was happening at UTEP. UTEP had a lot more Hispanics than any other (University of Texas System) school, and we were getting short changed with the money.

Q: What events happened before the protest? Why did it escalate to civil disobedience?

A: We did our research and during that time, I went to the board of regents meeting in Austin, and we gave a presentation with all the facts and statistics that we had and we were able to prove that what we were alleging was in fact true.

UTEP was getting less money than any other school in the system. And then we didn’t have any tenured professors of Hispanic origin. As a consequence, we formed La Mesa Directiva that consisted of faculty members, community members and student members, to press our demands as to what we wanted to happen at the university.

We were able to push for more funding for UTEP, we were able to kick the door open, so to speak, for a lot more Hispanics to attend college and we were able to push for some professors to become tenured. That’s why we had the demonstration.

Q: What did it take to plan a demonstration of that size?

A: We had several meetings; we determined what we were going to do, how we were going to do it and who was going to participate. Once we decided that we were going to go to the Administration Building to present our demands, we felt that they might go ahead and not meet with us, and in that case we would take over the Administration Building so that they would.

We met with local attorneys in town—we arranged for us to be bonded out if we were to get arrested because we knew that would be a risk.

We took a risk, those of us who decided to go to the building, because at the time, it was a criminal charge that they charged us with. We knew that we were putting our future in jeopardy, but we decided to do it anyways.

The Aftermath

More than 3,000 students joined in MEChA’s protest that day. As a result, the Chicano Studies Program was instituted, a tutoring center was created, the university received more funding from the UT System and more Hispanic teachers were hired and considered for tenure. But the demands of the students were not met overnight.

Sarabia said a second rally was formed shortly after the one that occurred on Dec. 3, when the group saw that their demands weren’t being met. The rally began at the UTEP Union, but before the protesters could leave the building, state troopers met them at the door and threatened to shoot them if they carried out their plan to march to the Administration Building.

After the protest, Sarabia and others joined forces with the MEChA group at UT Austin and attended another board of regents meeting. This time things accelerated, Sarabia said. The UT System began meeting more of the students’ demands.

The protesters later went on to achieve several individual accomplishments.

One such activist went on to become a New Mexico state representative. Rep. Patricia Roybal Caballero, D-N.M., of Albuquerque said her time participating in MEChA and the 1971 protest influenced the course of her life in many ways. Roybal Caballero was one of the original founders of the MEChA chapter at UTEP.

Patricia Roybal Caballero,

the torchbearer

Q: What was your experience like with MEChA leading up to the December 1971 protest?

A: Our belief was that we needed to be closely related to everything in the community and the students needed to be associated with the community.

We were going to school at the higher level so that we could go back and strengthen our communities, and we felt strongly about keeping those values through the entire university experience. We created a model that was the Chicano affairs program—it was an umbrella program that included the entire student service component and the Chicano studies component. Chicano affairs would be the oversight to hold the university accountable to the services and programs that we instituted with the university so that we could increase our population and that they were retained. We also developed the initial curriculum for the Chicano Studies Program. All this time we were putting our proposal forward at UTEP, and every time we were met with opposition.

Q: What did participating in this protest mean to you?

A: It was exciting to know that in this country, we had the right to be doing what we were doing. And for me in particular, my father was in Vietnam fighting his third war—he was in WWII and Korea and he served two tours of duty in Vietnam with the Special Forces. For me it was: I’m exercising exactly what my father, as we speak, is fighting in Vietnam for—for me to have the right to be represented and the right to be present at the university and in all entities in our society. So, for me, it was even more important to be doing what I was doing.

Q: What is your opinion on the aftermath of the protest? Do you think the university handled your demands appropriately?

A: The immediate aftermath—obviously we succeeded in some areas—but ultimately it has been one constant battle after another at that university. Nothing has been met with ease; nothing has been accepted without opposition. I’m sorry to say that it has not been a steady acceptance.

It has taken all this time just to increase our presence on campus, to increase the number of our graduates and the fields in which they are going. The degree of resistance is different, and the degree of opposition is different. However, racism is still alive and well, not just in El Paso but around the country. It’s going to take generations—just as it took generations to create the exploitative and divisionary aspects we face in society—it’s going to take generations to turn that around. Even though some things were met, it has been a long road and every generation of Chicano students that have been there since us, has had a history of struggle on that campus.

Q: What advice do you give present-day Chicano students?

A: The Chicano students of today have to be proud and espouse their cultural history, their cultural traditions and their language. As our population grows, there’s even more of a sense of urgency for us to be able to continue from a position of strength. Chicano students of today have to understand that when they speak and whatever they are doing, they are coming from a position of strength. They are not a minority, they are not underrepresented, they are not in the negatives. We are a very strong population. We have survived for generations. We have a long history of struggle in this country—and that is a position of strength, not a weakness.

Jasmine Aguilera may be reached at [email protected].