American scholar of Chicana feminism, cultural theory, and queer theory, Gloria Anzaldúa once wrote: “Alienated from her mother culture, ‘alien’ in the dominant culture, the woman of color does not feel safe within the inner life of her self. Petrified, she can’t respond, her face caught between los intersticios, the spaces between the different worlds she inhabits.”

In her writing, she often explored the idea of not belonging, not being enough as a borderland Chicana and being stuck between two worlds.

“Ni de aquí, ni de allá”. This is a phrase that is often used among Chicanos to describe the feeling of not fully belonging to a culture. Many say it can feel like they are walking two different paths. People who move from Mexico to the U.S., often describe it as leaving a piece of themselves behind, and sometimes they struggle with reconnecting with that part of themselves.

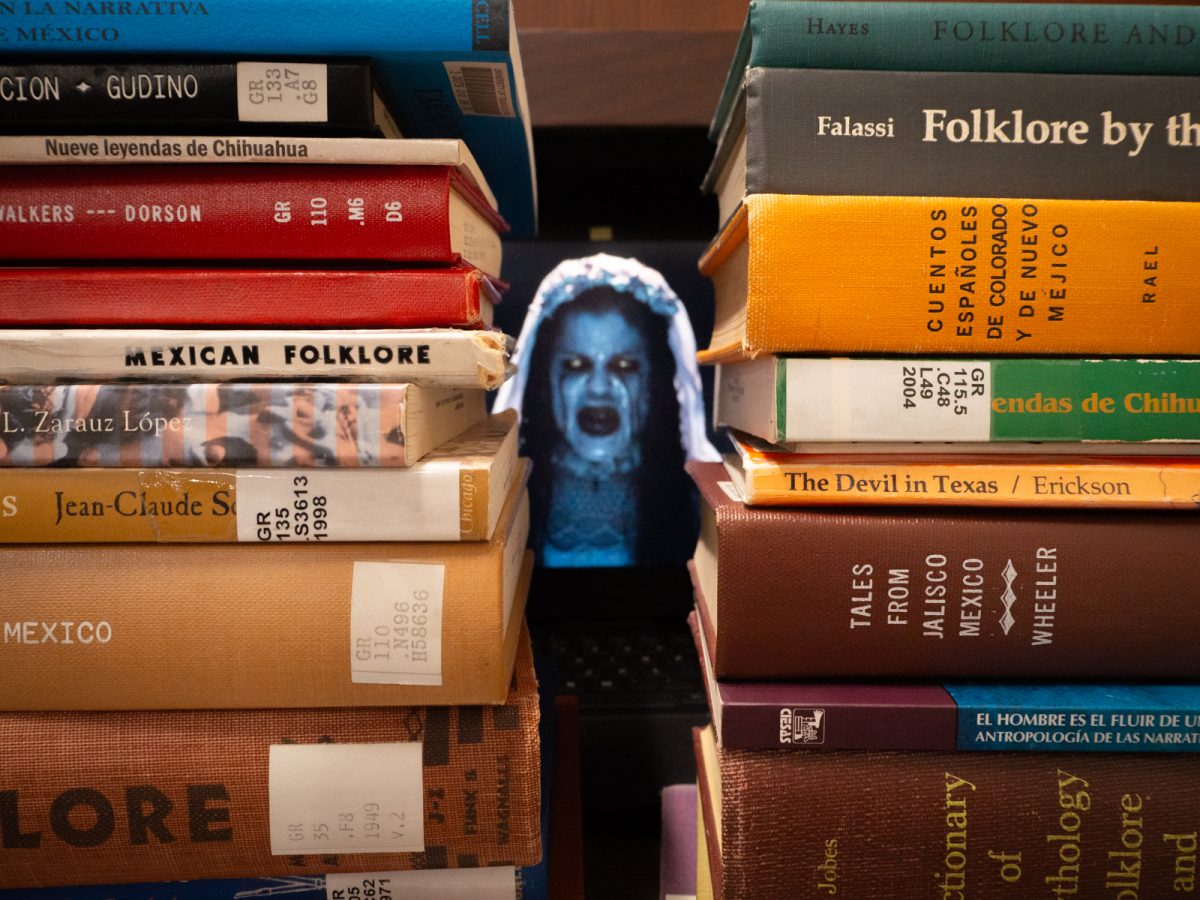

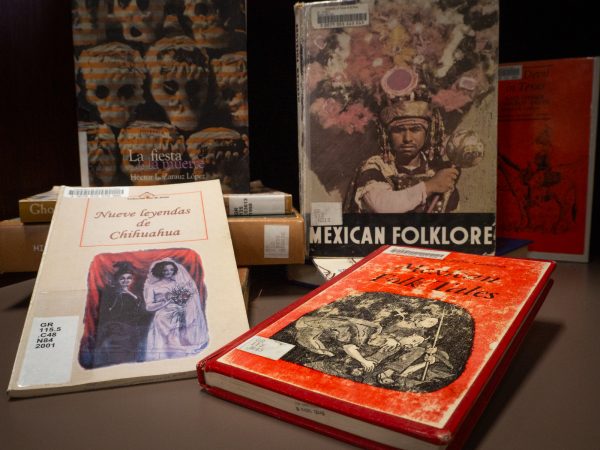

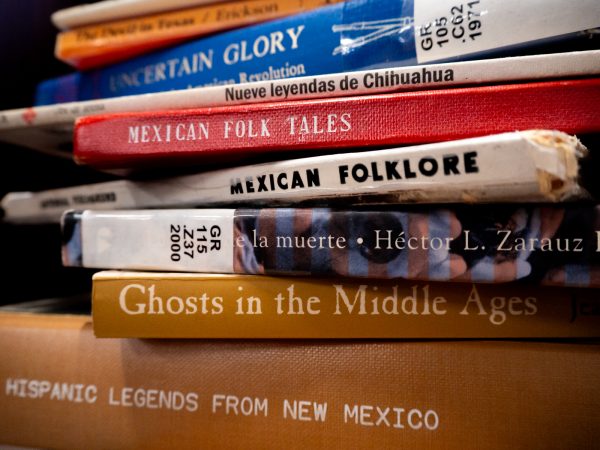

Folklore or leyendas in Spanish are one way for Chicanos to connect with and remember their cultural roots.

The popular franchise “Las Leyendas” has produced films such as “La Leyenda de la Nahuala” (2007) and “La Leyenda de la Llorona” (2011), as well as TV shows like “Las Leyendas: El Origen” (2022) and “Las Leyendas de los Chaneques (2023). These pieces of media have become ubiquitous with Mexican culture and are the subject of memes, gifs and even merchandise. Because of their presence, they have also transcended to Chicano culture.

“La Leyenda de la Llorona” for instance, tells the tale of a woman who out of a fit of anger, drowns her children in a lake and is cursed to haunt the lake for eternity as she cries out, “¡Ay mis hijos!”. While it is a Mexican leyenda, it has evolved with and adapted to changing times and cultures.

Irma Montelongo, Ph.D., a professor in the Chicano Studies Department, said that the details of folklore can vary from community to community.

“Everybody knows the story of La Llorona, but it kind of changes, it kind of adapts to the community,” Montelongo said. “Maybe the Mexican community in Tusan knows the Llorona, but just a little bit differently than the way it is in El Paso. We adapt our folklore to our spaces.”

Chicanos, or members of other communities, often take long-told tales with clear messages, such as La Llorona, El Cucuy and El Chupacabras, and give them their own spin. This allows them to keep their cultural roots, while also making it more relatable. For example, the Llorona might now be said to cry in the Rio Grande rather than crying by a lake or other body of water.

Leyendas can also be a way for people to dream of something that was lost. For example, the mythical homeland of Chicanos, Aztlan folklore focuses on the idea that Chicanos have been in their land for far longer than people realize. Similar to the city of Atlantis, people speculate that Aztlan is located somewhere in the southwest. This leyenda is rooted in fact, since indigenous tribes were in the land of the United States long before colonizers came. So for Chicanos, Aztlan presents a way to stay connected with their ancestors.

“The antepasados, our raíces, our people are from this area. We have this connection to this area. This is where we come from. We’re not new to this region, we’ve always been here,” Montelongo said.

While the shock of biculturalism can sometimes leave Chicanos wondering who they are or where they belong. It is seen that folklore can ground and connect them to their Mexican heritage, serving as a reminder of the indigenous peoples they come from. Folklores serve as oral history, while people may never know if they are entirely true, there is truth within them.

Aylinne Morales is a contributor at the Prospector and may be reached at [email protected].